“Meaningful inclusion” is a term that supports the premise that all children should receive an education in the least restrictive environment. To achieve this goal, social barriers must be hurdled and meaningful instruction must occur. Anne Howard, PT, PhD tackled this issue in her Therapro Saturday Seminar last week entitled: Providing Optimal Services and Supports for Students with Down Syndrome in Educational Settings.

Dr. Howard’s extensive educational background, beginning as a physical therapist, then becoming an educator, to receiving her doctorate in disability policy, has provided the background for pursuing her interest in those with Down syndrome now as a college professor and consultant to families and school systems. In addition, Anne serves on the Massachusetts Down Syndrome Congress (MDSC) Education Task Force and contributed to the MDSC Educator’s Manual. This manual provides a comprehensive look at the complex learning profile of students with Down syndrome, as well as provides information around educational considerations that are based upon research-proven best practices.

Anne is also the President of the Board of Directors for the Federation for Children with Special Needs. With her glowing credentials and experience, Anne proved to be a formidable speaker and expert on Down syndrome.

Attendees at the seminar received a comprehensive review of common learning characteristics and associated physical and health care needs specific to students with Down syndrome. Dr. Howard provided an interactive seminar, inviting attendees to share their perceptions of students with Down syndrome and asking them to determine what they wanted to learn about students with Down syndrome. She discussed strategies to facilitate independence using visual supports and self-management. Anne reviewed some basics on Down syndrome with some surprising issues that have come to light. For example, she noted that children with Down syndrome have a greater prevalence of ASD, with some statistics cited that up to 18% of children with Down syndrome have a co-occurring diagnosis of Autism.

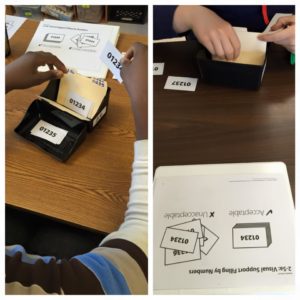

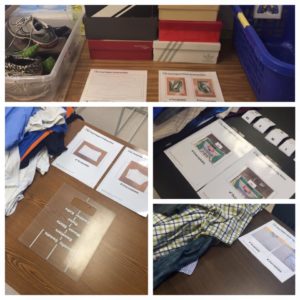

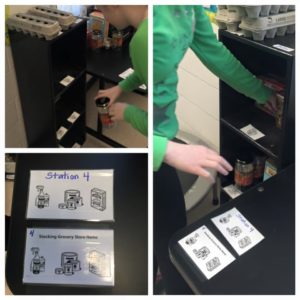

Anne discussed encouraging research that shows that fully inclusive education, special teaching approaches that address areas of weakness, and providing opportunities for success can change the typical profile of a child with Down syndrome, citing studies by Buckley, Bird, and Sacks in Down Syndrome Research and Practice, 2006. A chart with “Characteristics of a typical learning profile” with areas defined as Communication, Socialization, Learning and Memory, and Motor was presented along with strategies to address the targeted areas. For example, if a student has motor weakness characterized by decreased muscle tone which makes writing difficult, along with having shorter fingers, strategies for learning might include providing adequate postural support, with appropriate seating, motor breaks with tone building activities, and use of adapted materials for handwriting including a slant surface, hand grips, or keyboarding. In addition, she advocated the use of visual supports, which are available for a longer time period for the student, versus using verbal or auditory cues alone. For example, sticky notes, diagrams on the board, photos, calendar, clock /timer, decrease the need for verbal cues. Visual supports are readily available to the student without the need for use of working memory or retrieval of information, which may be difficult for some students.

Finally, Anne provided a Behavior Profile associated with Down syndrome, enumerating strengths, learned behaviors, and then identified strategies that support productive behavior in students with Down syndrome. Students can be taught to self-manage with strategies like self monitoring/self-recoding, self-evaluation, and self-reinforcement. She suggested that the key is to empower the student by letting him/her know what is expected. By being proactive, negative behaviors can be averted and targeted behaviors can be reinforced. She noted that the key to developing acceptable and positive behaviors is to build desired behaviors, versus just responding to negative behavior.

Considering the student with Down syndrome and how to help him/her succeed in an inclusion model involves a number of factors. Understanding the common characteristics and challenges of this diagnosis is a good starting point. From there, a wide variety of positive strategies can be implemented to help make the educational process meaningful and fulfilling for the individual student.

Anne has generously provided this link to her PowerPoint slides.

Here are some remarks from attendees:

“I really appreciated Anne’s diverse background. She was able to present the information from a different perspective than I might normally consider.” Micaela C., Physical Therapist

“Helpful as a student to hear real-world application from professionals in practice who were in attendance. Also great to see theory learned in the classroom reinforced.” Sam J., OT student

“Clear, relevant, evidence based info/treatment strategies.” Mary T., Occupational Therapist

“Dr. Howard provided & presented the basic background info for DS well. She provided useful examples for behavior management for children with DS that I hope to implement with my students.” Anonymous, PT

Thank you, Anne!

Filomena Connor, MS, OTR/L