I came across Educational Kinesiology in the early 1990s when searching for tools or techniques to help heal from a chronic illness. Little did I know that it would become an integral part of much of my OT practice. I began with Brain Gym I and II and loved the fact that the two trainers in South Africa were experienced occupational therapists trained in both SI and NDT.

Brain Gym is wonderful for assisting with goal setting, whole brain learning, stress release, and re-patterning. Although there is a specific process to follow, many of the exercises are both beneficial and transferable into a regular OT session. One that I use a lot is the Lazy 8 – a figure eight that lies on its side like the infinity sign.

What is the Brain Gym figure eight used for?

In Brain Gym terms, the Lazy 8 turns on or activates the eyes while also crossing the mid-line.

It can be used to improve ocular motor function, which assists with reading, and crossing the mid-line improves integration between the two hemispheres of the brain.

The repeated action of the Lazy 8 is also very calming. It can be used in several different formats – using the eyes, drawing the figure of 8 in the appropriate orientation, and in motion, as we shall see shortly.

The Lazy 8 can also be carried out as a motor activity, having the client walk, skip, or run around a figure eight. I love to use two hoops placed side by side on the floor to provide a visual cue. Varying the space between the hoops elongates or enlarges the figure eight. Make it more fun by having the client clap while moving around the figure of eight in time to music.

For added motor integration, combine the cross crawl with the Lazy 8. This often has to be carried out in stages:

- Having the client carry out their cross crawl while standing until they are sufficiently at ease with the exercise

- Upgrade to carrying out the cross crawl while walking on a straight line

- Upgrade further to doing cross crawls while walking a figure eight

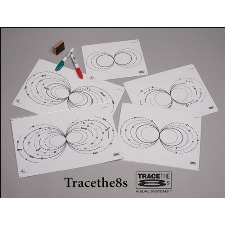

When I first began using components of Brain Gym in my treatment sessions, I would often make up my own worksheets. I am delighted to discover that Therapro has a range of products that bring the figure eight into practice for all occupational therapists. Two examples include:

When I first began using components of Brain Gym in my treatment sessions, I would often make up my own worksheets. I am delighted to discover that Therapro has a range of products that bring the figure eight into practice for all occupational therapists. Two examples include:

The development of these tools shows how Brain Gym is becoming accepted as a beneficial modality to use within OT. It also provides an added level of professionalism, which is important for anyone who is skeptical of either how Brain Gym combines with OT or the extent to which OT itself is a recognized profession.

Once clients are familiar with the Lazy 8 through either Trace the 8s or Race the 8s, introducing the Alphabet 8 helps improve their motor memory. The Alphabet 8 incorporates lower-case letters with the Lazy 8 and is wonderful as a pre-writing activity to enhance work to meet writing goals. It’s designed for English letters but, with some creativity and practice, cursive letters for Hebrew can also be used. Note, I am not sufficiently familiar with other alphabets to know how well they can be used in the Alphabet 8.

Once clients are familiar with the Lazy 8 through either Trace the 8s or Race the 8s, introducing the Alphabet 8 helps improve their motor memory. The Alphabet 8 incorporates lower-case letters with the Lazy 8 and is wonderful as a pre-writing activity to enhance work to meet writing goals. It’s designed for English letters but, with some creativity and practice, cursive letters for Hebrew can also be used. Note, I am not sufficiently familiar with other alphabets to know how well they can be used in the Alphabet 8.

I mentioned earlier the benefit of improving a sense of calm. The rhythmic movement of drawing or moving in the Brain Gym figure eight pattern is a wonderful addition to your toolbox for assisting clients in need of stress management and improving relaxation.

Guest Blogger: Shoshanah Shear

Occupational Therapist, healing facilitator, certified infant massage instructor, freelance writer, author of “Healing Your Life Through Activity – An Occupational Therapist’s Story” and co-author of “Tuvia Finds His Freedom”.

Occupational Therapist, healing facilitator, certified infant massage instructor, freelance writer, author of “Healing Your Life Through Activity – An Occupational Therapist’s Story” and co-author of “Tuvia Finds His Freedom”.